Malaka Gharib makes sense of a complicated world by making art. As a journalist, zine-maker, and graphic novelist, Malaka is in her element writing and illustrating her unique perspective of the world around her. We had the pleasure of learning about her creative approach to storytelling in the latest edition of Elevating Stories–a series of talks with authors, experts, and creators held at 2A.

Malaka traveled to Seattle from her home of Washington, D.C. to present at the Short Run Comix and Arts Festival, the city’s preeminent convention on alternative comics and handmade books of all kinds. In addition to the festival and speaking at 2A, she also used her trip to promote her new graphic memoir about growing up as a first-generation Egyptian-Filipino American, I Was Their American Dream. In an authentic conversation, Malaka revealed these lessons she’s learned from finding her creative identity and professionally publishing her first book.

You can’t always depend on your day job to be a creative outlet

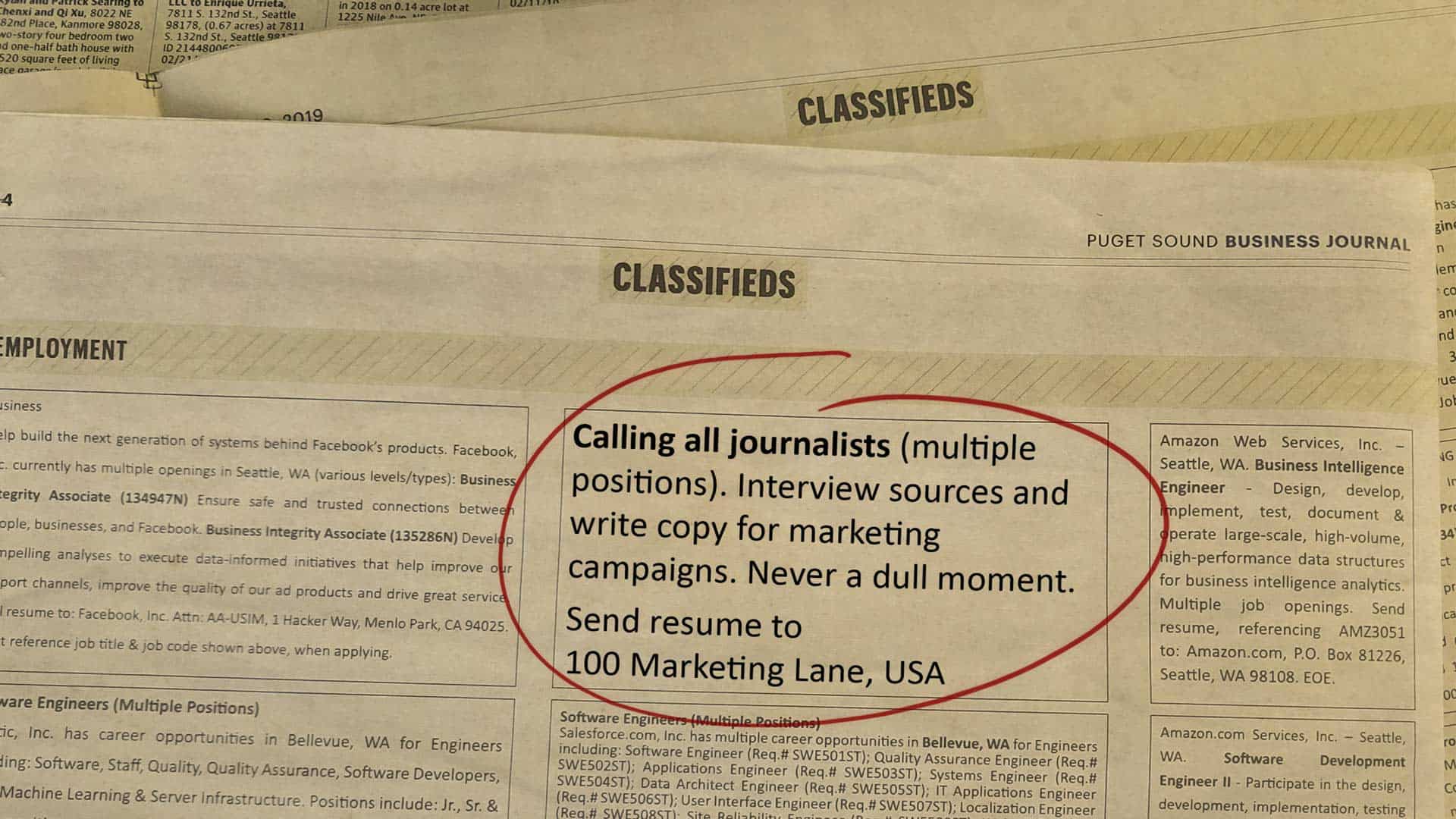

After graduating from college as a magazine journalism major during the 2008 financial crisis, Malaka realized that she couldn’t rely on her 9-to-5 job for creative expression. So she figured out how to do it in her free time. By carving out time to write and draw on her own accord, she made zines and art that truly satisfied her own personal agenda.

Making art helps us persevere

As the child of Egyptian and Filipino immigrants, Malaka struggled to make sense of her personal identity growing up. She learned as a teenager that following creative pursuits could help her understand and celebrate her uncommon background. After Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric helped him become president, Malaka knew she had to write a book about her upbringing that served as a counter argument. Self-expression enables catharsis, and Malaka was able to cope with the state of the world by taking on the biggest creative project of her life.

Zines can be storytelling building blocks

Zines are self-published magazines that don’t follow print conventions, which makes them flexible tools for storytelling especially suited to people tight on time like Malaka. To quickly get her creative energy out, Malaka’s made a habit of creating mini comic zines from a single sheet of paper during idle moments. When she faced the daunting task of creating a 160-page graphic novel, Malaka structured it as a compilation of eight zines. By breaking the novel into familiar subcomponents, she was able to control her focus and organization.

Collaborate, but don’t compromise your vision

Writing and illustrating your first novel is inherently a learning process. And for someone used to the DIY nature of zines, working with dozens of book agents, publishers, designers, and editors made for a dizzying experience. More than 60 people contributed to the creation of her book, and their guidance was sometimes in conflict. At one point, her work-in-progress novel was a problem she just wanted to throw money at to fix. But after taking command of her vision, she put the right stakeholders in place to get the best version of her book across the finish line.

To the uninformed, writing a book sounds romantic. However, Malaka’s uncensored depiction of writing and drawing a graphic memoir took us behind the curtain to understand how messy the creative process can be. She candidly shared obstacles in her journey as a storyteller, but also proved that creating something that beautifully captures your perspective is worth the struggle.